- Home

- John le Carré

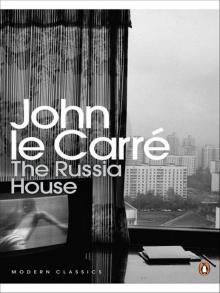

The Russia House

The Russia House Read online

JOHN LE CARRÉ

The Russia House

with an Afterword by the author

PENGUIN BOOKS

Contents

Foreword

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Afterword

PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

THE RUSSIA HOUSE

John le Carré was born in 1931. His third novel, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, secured him a worldwide reputation, which was consolidated by the acclaim for his trilogy Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, The Honourable Schoolboy and Smiley’s People. His later novels include The Constant Gardener, Absolute Friends, The Mission Song and A Most Wanted Man. Our Kind of Traitor is his most recent novel.

For Bob Gottlieb, a great editor

and a long-suffering friend

‘Indeed, I think that people want peace so much that one of these days governments had better get out of their way and let them have it.’

Dwight D. Eisenhower

‘One must think like a hero to behave like a merely decent human being.’

May Sarton

Foreword

Acknowledgements in novels can be as tedious as credits at the cinema, yet I am constantly touched by the willingness of busy people to give their time and wisdom to such a frivolous undertaking as mine, and I cannot miss this opportunity to thank them.

I recall with particular gratitude the help of Strobe Talbott, the illustrious Washington journalist, Sovietologist and writer on nuclear defence. If there are errors in this book they are surely not his, and there would have been many more without him. Professor Lawrence Freedman, the author of several standard works on the modern conflict, also allowed me to sit at his feet, but must not be blamed for my simplicities.

Frank Geritty, for many years an agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, introduced me to the mysteries of the lie-detector, now sadly called the polygraph, and if my characters are not as complimentary about its powers as he is, the reader should blame them, not him.

I must also offer a disclaimer on behalf of John Roberts and his staff at the Great Britain-USSR Association, of which he is Director. It was he who accompanied me on my first visit to the USSR, opening all sorts of doors for me that might otherwise have stayed shut. But he knew nothing of my dark intent, neither did he probe. Of his staff, I may mention particularly Anne Vaughan.

My Soviet hosts at the Writers’ Union showed a similar discretion, and a largeness of spirit that took me by surprise. Nobody who visits the Soviet Union in these extraordinary years, and is privileged to conduct the conversations that were granted me, can come away without an enduring love for its people and a sense of awe at the scale of the problems that face them. I hope that my Soviet friends will find reflected in this fable a little of the warmth that I felt in their company, and of the hopes we shared for a saner and more companionable future.

Jazz is a great unifier and I did not want for friends when it came to Barley’s saxophone. Wally Fawkes, the celebrated cartoonist and jazz player, lent me his musician’s ear, and John Calley his perfect pitch both in words and music. If such men would only run the world I should have no more conflicts to write about.

John le Carré

1

In a broad Moscow street not two hundred yards from the Leningrad station, on the upper floor of an ornate and hideous hotel built by Stalin in the style known to Muscovites as Empire During the Plague, the British Council’s first ever audio fair for the teaching of the English language and the spread of British culture was grinding to its excruciating end. The time was half past five, the summer weather erratic. After fierce rain showers all day long, a false sunlight was blazing in the puddles and raising vapour from the pavements. Of the passers-by, the younger ones wore jeans and sneakers, but their elders were still huddled in their warms.

The room the Council had rented was not expensive but neither was it appropriate to the occasion. I have seen it – Not long ago, in Moscow on quite another mission, I tiptoed up the great empty staircase and, with a diplomatic passport in my pocket, stood in the eternal dusk that shrouds old ballrooms when they are asleep – With its plump brown pillars and gilded mirrors, it was better suited to the last hours of a sinking liner than the launch of a great initiative. On the ceiling, snarling Russians in proletarian caps shook their fists at Lenin. Their vigour contrasted unhelpfully with the chipped green racks of sound cassettes along the walls, featuring Winnie-the-Pooh and Advanced Computer English in Three Hours. The sackcloth sound-booths, locally procured and lacking many of their promised features, had the sadness of deck chairs on a rainy beach. The exhibitors’ stands, crammed under the shadow of an overhanging gallery, seemed as blasphemous as betting shops in a tabernacle.

Nevertheless a fair of sorts had taken place. People had come, as Moscow people do, provided they have the documents and status to satisfy the hard-eyed boys in leather jackets at the door. Out of politeness. Out of curiosity. To talk to Westerners. Because it is there. And now on the fifth and final evening the great farewell cocktail party of exhibitors and invited guests was getting into its stride. A handful of the small nomenclatura of the Soviet cultural bureaucracy was gathering under the chandelier, the ladies in their beehive hairstyles and flowered frocks designed for slenderer frames, the gentlemen slimmed by the shiny French-tailored suits that signified access to the special clothing stores. Only their British hosts, in despondent shades of grey, observed the monotone of socialist austerity. The hubbub rose, a brigade of pinafored governesses distributed the curling salami sandwiches and warm white wine. A senior British diplomat who was not quite the Ambassador shook the better hands and said he was delighted.

Only Niki Landau among them had withheld himself from the celebrations. He was stooped over the table in his empty stand, totting up his last orders and checking his dockets against expenses, for it was a maxim of Landau’s never to go out and play until he had wrapped up his day’s business.

And in the corner of his eye – an anxious blue blur was all that she amounted to – this Soviet woman he was deliberately ignoring. Trouble, he was thinking as he laboured. Avoid.

The air of festivity had not communicated itself to Landau, festive by temperament though he was. For one thing, he had a lifelong aversion to British officialdom, ever since his father had been forcibly returned to Poland. The British themselves, he told me later, he would hear no wrong of them. He was one of them by adoption and he had the poker-backed reverence of the convert. But the Foreign Office flunkeys were another matter. And the loftier they were, and the more they twitched and smirked and raised their stupid eyebrows at him, the more he hated them and thought about his dad. For another thing, if he had been left to himself, he would never have come to the audio fair in the first place. He’d have been tucked up in Brighton with a nice new little friend he had, called Lydia, in a nice little private hotel he knew for taking little friends.

‘Better to keep our powder dry till the Moscow book fair in September,’ Landau had advised his clients at their headquarters on the Western by-pass. ‘The Russkies love a book, you see, Bernard, but the audio market scares them and they aren’t geared for it. Go in with the book fair, we’ll clean up. Go in with the audio fair, we’re dead.’

But Landau’s clients were young and rich and did not believe in death. ‘Niki boy,’ said Bernard,

walking round behind him and putting a hand on his shoulder, which Landau didn’t like, ‘in the world today, we’ve got to show the flag. We’re patriots, see, Niki? Like you. That’s why we’re an offshore company. With the glasnost today, the Soviet Union, it’s the Mount Everest of the recording business. And you’re going to put us on the top, Niki. Because if you’re not, we’ll find somebody who will. Somebody younger, Niki, right? Somebody with the drive and the class.’

The drive Landau had still. But the class, as he himself was the first to tell you, the class, forget it. He was a card, that’s what he liked to be. A pushy, short-arsed Polish card and proud of it. He was Old Nik the cheeky chappie of the Eastward-facing reps, capable, he liked to boast, of selling filthy pictures to a Georgian convent or hair tonic to a Rumanian billiard ball. He was Landau the undersized bedroom athlete, who wore raised heels to give his Slav body the English scale he admired, and ritzy suits that whistled ‘here I am’. When Old Nik set up his stand, his travelling colleagues assured our unattributable enquirers, you could hear the tinkle of the handbell on his Polish vendor’s barrow.

And little Landau shared the joke with them, he played their game. ‘Boys, I’m the Pole you wouldn’t touch with a barge,’ he would declare proudly as he ordered up another round. Which was his way of getting them to laugh with him. Instead of at him. And then most likely, to demonstrate his point, he would whip a comb from his top pocket and drop into a crouch. And with the aid of a picture on the wall, or any other polished surface, he’d sweep back his too-black hair in preparation for fresh conquest, using both his little hands to coax it into manliness. ‘Who’s that comely one I’m looking at over there in the corner, then?’ he’d ask, in his godless blend of ghetto Polish and East End cockney. ‘Hullo there, sweetheart! Why are we suffering all alone tonight?’ And once out of five times he’d score, which in Landau’s book was an acceptable rate of return, always provided you kept asking.

But this evening Landau wasn’t thinking of scoring or even asking. He was thinking that yet again he had worked his heart out all week for a pittance – or as he put it more graphically to me, a tart’s kiss. And that every fair these days, whether it was a book fair or an audio fair or any other kind of fair, took a little more out of him than he liked to admit to himself, just as every woman did. And gave him a fraction too little in return. And that tomorrow’s plane back to London couldn’t come too soon. And that if this Russian bird in blue didn’t stop insinuating herself into his attention when he was trying to close his books and put on his party smile and join the jubilant throng, he would very likely say something to her in her own language that both of them would live to regret.

That she was Russian went without saying. Only a Russian woman would have a plastic perhaps-bag dangling from her arm in readiness for the chance purchase that is the triumph of everyday life, even if most perhaps-bags were of string. Only a Russian would be so nosy as to stand close enough to check a man’s arithmetic. And only a Russian would preface her interruption with one of those fastidious grunts, which in a man always reminded Landau of his father doing up his shoe laces, and in a woman, Harry, bed.

‘Excuse me, sir. Are you the gentleman from Abercrombie & Blair?’ she asked.

‘Not here, dear,’ said Landau without lifting his head. She had spoken English, so he had spoken English in return, which was the way he played it always.

‘Mr. Barley?’

‘Not Barley, dear. Landau.’

‘But this is Mr. Barley’s stand.’

‘This is not Barley’s stand. This is my stand. Abercrombie & Blair are next door.’

Still without looking up, Landau jabbed his pencil-end to the left, towards the empty stand on the other side of the partition, where a green and gold board proclaimed the ancient publishing house of Abercrombie & Blair of Norfolk Street, Strand.

‘But that stand is empty. No one is there,’ the woman objected. ‘It was empty yesterday also.’

‘Correct. Right on,’ Landau retorted in a tone that was final enough for anybody. Then he ostentatiously lowered himself further into his account book, waiting for the blue blur to remove itself. Which was rude of him, he knew, and her continuing presence made him feel ruder.

‘But where is Scott Blair? Where is the man they call Barley? I must speak to him. It is very urgent.’

Landau was by now hating the woman with unreasoning ferocity.

‘Mr. Scott Blair,’ he began as he snapped up his head and stared at her full on, ‘more commonly known to his intimates as Barley, is awol, madam. That means absent without leave. His company booked a stand – yes. And Mr. Scott Blair is chairman, president, governor-general and for all I know lifetime dictator of that company. However, he did not occupy his stand –’ but here, having caught her eye, he began to lose his footing. ‘Listen, dear, I happen to be trying to make a living here, right? I am not making it for Mr. Barley Scott Blair, love him as I may.’

Then he stopped, as a chivalrous concern replaced his momentary anger. The woman was trembling. Not only with the hands that held her brown perhaps-bag, but at the neck, for her prim blue dress was finished with a collar of old lace and Landau could see how it shook against her skin and how her skin was actually whiter than the lace. Yet her mouth and jaw were set with determination and her expression commanded him.

‘Please, sir, you must be very kind and help me,’ she said as if there were no choice.

Now Landau prided himself on knowing women. It was another of his irksome boasts but it was not without foundation. ‘Women, they’re my hobby, my life’s study and my consuming passion, Harry,’ he confided to me, and the conviction in his voice was as solemn as a Mason’s pledge. He could no longer tell you how many he had had, but he was pleased to say that the figure ran into the hundreds and there was not one of them who had cause to regret the experience. ‘I play straight, I choose wisely, Harry,’ he assured me, tapping one side of his nose with his forefinger. ‘No cut wrists, no broken marriages, no harsh words afterwards.’ How true this was, nobody would ever know, myself included, but there can be no doubt that the instincts that had guided him through his philanderings came rushing to his assistance as he formed his judgments about the woman.

She was earnest. She was intelligent. She was determined. She was scared, even though her dark eyes were lit with humour. And she had that rare quality which Landau in his flowery way liked to call the Class That Only Nature Can Bestow. In other words, she had quality as well as strength. And since in moments of crisis our thoughts do not run consecutively but rather sweep over us in waves of intuition and experience, he sensed all these things at once and was on terms with them by the time she spoke to him again.

‘A Soviet friend of mine has written a creative and important work of literature,’ she said after taking a deep breath. ‘It is a novel. A great novel. Its message is important for all mankind.’

She had dried up.

‘A novel,’ Landau prompted. And then, for no reason he could afterwards think of, ‘What’s its title, dear?’

The strength in her, he decided, came neither from bravado nor insanity but from conviction.

‘What’s its message then, if it hasn’t got a title?’

‘It concerns actions before words. It rejects the gradualism of the perestroika. It demands action and rejects all cosmetic change.’

‘Nice,’ said Landau, impressed.

She spoke like my mother used to, Harry: chin up and straight into your face.

‘In spite of glasnost and the supposed liberalism of the new guidelines, my friend’s novel cannot yet be published in the Soviet Union,’ she continued. ‘Mr. Scott Blair has undertaken to publish it with discretion.’

‘Lady,’ said Landau kindly, his face now close to hers. ‘If your friend’s novel is published by the great house of Abercrombie & Blair, believe me, you can be assured of total secrecy.’

He said this partly as a joke he couldn’t resist and partly because

his instincts told him to take the stiffness out of their conversation and make it less conspicuous to anybody watching. And whether she understood the joke or not, the woman smiled also, a swift warm smile of self-encouragement that was like a victory over her fears.

‘Then, Mr. Landau, if you love peace, please take this manuscript with you back to England and give it immediately to Mr. Scott Blair. Only to Mr. Scott Blair. It is a gift of trust.’

What happened next happened quickly, a street-corner transaction, willing seller to willing buyer. The first thing Landau did was look behind her, past her shoulder. He did that for his own preservation as well as hers. It was his experience that when the Russkies wanted to get up to a piece of mischief, they always had other people close by. But his end of the assembly room was empty, the area beneath the gallery where the stands were was dark and the party at the centre of the room was by now in full cry. The three boys in leather jackets at the front door were talking stodgily among themselves.

His survey completed, he read the girl’s plastic name badge on her lapel, which was something he would normally have done earlier but her black-brown eyes had distracted him. Yekaterina Orlova, he read. And underneath, the word ‘October’, given in both English and Russian, this being the name of one of Moscow’s smaller State publishing houses specialising in translations of Soviet books for export, mainly to other Socialist countries, which I am afraid condemned it to a certain dowdiness.

Next he told her what to do, or perhaps he was already telling her by the time he read her badge. Landau was a street kid, up to all the tricks. The woman might be as brave as six lions and by the look of her probably was. But she was no conspirator. Therefore he took her unhesitatingly into his protection. And in doing so he spoke to her as he would to any woman who needed his basic counsel, such as where to find his hotel bedroom or what to tell her hubby when she got home.

The Honorable Schoolboy

The Honorable Schoolboy The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories From My Life

The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories From My Life Single & Single

Single & Single The Spy Who Came in From the Cold

The Spy Who Came in From the Cold The Looking Glass War

The Looking Glass War The Night Manager

The Night Manager A Delicate Truth

A Delicate Truth A Perfect Spy

A Perfect Spy The Little Drummer Girl

The Little Drummer Girl Absolute Friends

Absolute Friends A Murder of Quality AND Call for the Dead

A Murder of Quality AND Call for the Dead The Russia House

The Russia House The Tailor of Panama

The Tailor of Panama Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy A Legacy of Spies

A Legacy of Spies The Mission Song

The Mission Song A Most Wanted Man

A Most Wanted Man John Le Carré: Three Complete Novels

John Le Carré: Three Complete Novels The Secret Pilgrim

The Secret Pilgrim A Small Town in Germany

A Small Town in Germany A Murder of Quality

A Murder of Quality Smiley's People

Smiley's People Agent Running in the Field

Agent Running in the Field The Spy Who Came in from the Cold s-3

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold s-3 The Pigeon Tunnel

The Pigeon Tunnel The Russia House - 13

The Russia House - 13 The Honourable Schoolboy

The Honourable Schoolboy Call For The Dead s-1

Call For The Dead s-1 Call for the Dead

Call for the Dead Call for the Dead - 1

Call for the Dead - 1